Electronic

Journals of Martial Arts and Sciences

Guelph School of Japanese Sword Arts, July, 2005

Considering Kata and The Flower of Battle

Deborah Klens-Bigman, Ph.D.

In the dark days of October 2001, I covered the Western Martial Arts

Workshops for FightingArts.com, the online martial arts journal.

The event was held at Riverside Church, a Gothic Revival warren of

mullioned windows and dim lighting on Manhattan's Upper West

Side. It was a difficult time generally, and some of the non-New

Yorker participants lamented the cancelled flights that prevented this

or that renowned European teacher from attending. We locals were

mostly happy to be alive. I found it comforting to immerse myself

in a mock-medieval world that was so removed from what the past month

had brought (but with some decidedly modern twists, such as women

participants' zeal for whacking each other (and men) with

broadswords).

During the course of the weekend, I happened on Bob Charron's class,

based on the teachings of the Flos Duellatorum (also called "Fior di

Battaglia") - in plain English - "The Flower of Battle." Charron

has spent many years researching, translating, and finally interpreting

the techniques laid out in this 15th century manuscript, authored (more

or less, as these things go), by a gentleman named Fiore dei

Liberi.

Fiore dei Liberi was an Italian master who was probably born around

1350 and died sometime before the mid-15th century. He was

well-educated for his times, as were his noble students.

According to the Flos, he studied combat arts for 40 years, and

successfully fought five famous duels before setting pen to paper – er

– vellum.

Fiore eventually attained a post as a master at arms at the court of

Nicolo III, Count D’Este. The Flos was written for the noble,

well-educated elite of this sophisticated court. It is the second

oldest manual of combat arts found thus far in the West (the oldest is

a 13th century fragment on fighting known as Tower Manuscript

I.33).

There are three extant versions of the Flos, named for the library

collections where they may be found: the Getty-Ludwig, the

Pierpont-Morgan, and the Pissani-Dossi (also called the Novati).

Scholars believe the three manuscripts were student copies made around

1410. Fiore’s original text has not been found, at least not

yet.

Of all of them, the Getty is apparently the most complete, containing

lavish illustrations and whole paragraphs of text describing fighting

techniques. The Morgan copy is less complete than the Getty,

containing fewer techniques, but it also has a fair amount of

descriptive text. The Pissani-Dossi version consists of the

illustrations with rhyming couplets rather than much prose text.

What is most interesting to students of the martial arts (and not just

Western martial arts) is the structure of the Flos. The

techniques themselves begin simply and become increasingly

complex. At the beginning of the Flos, the partners engage in

empty-hand techniques. As the MS continues, the partners advance

to daggers, then swords, and finally, to lance techniques on

horseback. It is not simply the progression that is worth noting;

Charrron's work on the Flos suggests that the principles and techniques

introduced in the empty-hand sections are utilized again and again with

various weapons. (I do not know if Charron's investigation has

led him to reproduce the horseback techniques for analysis. I think at

least, not yet.)

Techniques are depicted between individuals of unequal skill, since

this is, indeed, a teaching manual. One, who wears a crown, is

obviously a master, while the uncrowned partner is apparently, a

student, or “scholar.” In advanced techniques, both partners wear

crowns, with the higher-ranking person identified by a garter worn

under one knee. These later sections introduce counters to

previously successful techniques.

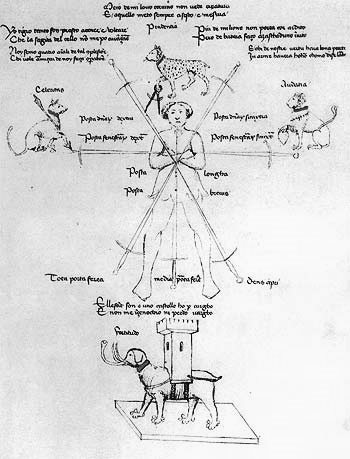

Then there is the segno, a plate inserted in the manuscript after the

illustrations of basic stances in the Novati version (Figure1).

Figure

1 - The Segno. Flos Duellatorum Pissani-Dosi MS Carta 17 A.

The plate shows a man surrounded by animals from a Medieval

bestiary. At the top, above the man’s head, is a lynx holding a

pair of calipers. At his right sits a lion and at his left hand,

a tiger, who holds an arrow. At his feet, there is an elephant,

bearing a castle on his back. According to Charron, the animals

represent philosophical concepts that would have been recognizable to

any educated person of the time, including Fiore’s noble

students.

The lynx, with his calipers, represents precision and reason. The

lion stands for justice and the law, while the tiger opposite him

represents speed and impetuosity. The assumption is that the

opposites control each other; i.e. the noble lion controls the wild

tiger. The elephant represents strength, stability and maybe also

reliability.

In between the animals are descriptions of the various guard positions

(what we would call kamae). The qualities of the different guards

relate to the characteristics of the animals depicted.

One of the differences often cited between Western and Asian martial

arts is the lack of metaphysical concepts underlying practice.

It’s like Fiore was reading our wistfully collective minds by providing

what was a state-of-the-art (at the time) philosophical basis for his

techniques.

But perhaps the most striking similarity to Asian martial arts

techniques is that the Flos was not written to teach battle skills per

se. The noble author was actually writing for, and teaching, his

noble patrons. The techniques outlined in the Flos could

conceivably be used for self-defense, but one of its key purposes was

to train young noblemen to acquit themselves well in tournaments and

other gentlemanly tests of martial skill, such as officially sanctioned

duels. While this might disappoint some, when you look at the

Flos it is not hard to believe. The Flos falls into line with

later Western manuals of swordsmanship in that people with means, who

might command, but are not that likely to actually fight on the

battlefield, would also have the resources and time to formally

train.

The Flos and Fiore’s career suggest he was teaching what in use,

temperament and structure was a Western martial art.

Unfortunately, in the way of things Western, Fiore’s art gave way to

more complicated, technically advanced means of fighting. Until

Charron, it seems no one really took seriously the idea that modern a

martial artist could bring Fiore’s ancient system back to life after

more than five centuries of neglect. So, here’s the

question: Can one really recreate a Western martial art?

Japanese martial practices are to some extent passed down - physically,

verbally, even pictorially in some cases. It is generally

acknowledged that not all elements of a given style have taken the

march through time. Some techniques have been preserved and

others given up (I think this is at least as likely as to assume they

have been “forgotten.”) Tamiya Ryu Iaijutsu, Tenshin Shoden

Katori Shinto Ryu and Yagyu Shinkage Ryu are examples of martial

traditions that have been in almost continuous practice. All of

these styles have scrolls created by teachers and students that have

been handed down through generations of practitioners, but, more

importantly, the techniques have been kinetically passed along.

Scrolls are not videotape; like Fiore’s Flos, they are keys to

technique and aids to memory rather than step-by-step how to’s.

Without physical practice, the scrolls (or vellum) have little meaning

in themselves.

Of course some other Japanese arts are also recreated (think judo) or

even invented (think ninpo). (1). Nearly all Japanese martial

practices lapsed during the Western Occupation after the Pacific

War. Some teachers died in the interim, some gave up. Some

modified techniques to make them less "martial," partly as a condition

of being allowed to teach them again, in some form, or out of a sense

of defying Japan's early 20th century militarism. A small few

were able to keep their practices more or less intact, through what I

expect was stubborn determination.

Some say all martial arts are "re-created," as the reasons for practice

have evolved over time, from possible actual fighting techniques to a

middle-class recreational pursuit, to pick an extreme line of

progression. Every generation finds its own reason for

practice. Looked at in this way, arguments for “authenticity” are

moot (see Donohue 1997).

That does not stop some practitioners from romantically yearning for

some sort of "authenticity," not realizing that it is a naïve

idea. Perhaps they hope against hope that some miraculously

detailed scroll, together with some ancient proto-video tape or magic

lantern show exists that shows some long-ago master performing

techniques as he originally conceived them.

Some may assume that a manual like the Flos affords more re- creative

detail than art forms that are passed down over time, like a fly caught

in amber. The Flos has several tantalizing aspects that would

make one think it was feasible - clear illustrations, a logical order,

a philosophical underpinning that, though based in a Medieval way of

thinking, is somewhat intelligible to us today. However, in all

likelihood, we are only perceiving a reasonable facsimile of what

Medieval teachers like Fiore were thinking. Charron's work shows

that it is possible to devise a system of martial arts training based

on Fiore's manuscript, even if questions of authenticity are obviously

impossible to settle with any finality.

But is the Flos actually better, somehow less intruded upon by modern

sensibilities, sitting forever in three antique book collections,

unsullied by interpretations of subsequent masters, serene in its glass

coffin - I mean case - like Snow White, until the handsome prince,

Charron or some other educated guy, wakes it with the kiss of acquired

knowledge?

It ain't necessarily so; at least, I don't think so.

Charron, for his part, has worked for years on interpreting the

techniques depicted in the Flos, but he is no way satisfied that he

understands what is really happening in some of them. His

research, done in comparison study with other techniques we know were

done in the same time period, has led him down enough blind alleys to

give him a healthy sense of self-doubt about what he is doing.

For example, the verses in the Pisani-Dossi (Novati) version that

accompany these ancient masters, students, and ubermasters are obscure

to say the least:

I’m well ready to throw you to the ground:

If you don’t have the contrary, I’ll do it now (Fiore n.d. 3).

Though there is some technical description in the other two versions,

there isn’t much, and a certain amount is obscured by both the dialects

(an ancient Northern Italian mixed with Latin) and the poetic

sensibility of the author. Charron has found that the

illustrations seem to be accurate, as far as they go.

But the biggest sticking point for Charron is the philosophical

concepts that surround and underpin Fiore's techniques. When I

asked Charron about the meanings in the segno, he responded that we had

to look at it with the mind of a Medieval noble. Easy for him to

say; unfortunately, I seem to have left my medieval mind in my other

suit. Here is the thing; When we look at the elephant that is

depicted at the feet of the man in the segno for example, we see an

animal that most of us have seen in zoos, a few of us have seen as work

animals (or maybe on TV), and virtually none of us have ever seen live,

in the wild. However, to a Medieval European, even a noble one,

an elephant was a fantastic creature. To cite an example, let’s

look at Medieval scholar Isidore’s description of far-away, more or

less human, creatures:

The Cynocephali are so called because they have dogs’ heads and their

very barking betrays them as beasts rather than men. These are

born in India…The Blemmyes, born in Libya, are believed to be headless

trunks, having mouth and eyes in the breast…(in Lowney 2005, 18)

We should note that Isidore’s Etymologies was consulted for up to ten

centuries after its 6th century composition. Scholar Chris Lowney

notes ten new editions of Isidore’s work were produced after the

1400’s, right up through Fiore’s time (2005, 19). That Fiore used

an elephant to represent stability and reliability may make sense to

us, we think, but what the hell did it mean to him? I mean really?

In my purely anecdotal and admittedly limited study of Japanese sword

kata (and in other classical movement forms, like Japanese classical

dance and Western ballet), the transmission from body to body has

worked well. Notation for ballet did not exist until recently and

even at that, interpreting it assumes, and requires, knowledge of

ballet technique, or it is all but useless. Moreover, it is by no

means a complete description. Movement notation is more like a

set of reference points to hang the memory of the dance on.

Revivals of say, Balanchine ballets are enormously influenced and

helped along by dancers who originally took part in them. They,

in turn, train other dancers, who, in turn, will pass along knowledge

of Balanchine's techniques and choreography to generations to come (at

least, as long as people are buying season tickets). The tragedy

of Martha Graham's company not being allowed to perform her work due to

a copyright dispute is not that we simply can't see it, but that it may

be lost altogether in twenty years or so, as the people who trained

with her are unable to pass it, physically, along. Anyone who

sees live dance as opposed to film or videotaped performances knows

exactly what I mean. Video is the vellum manuscript of

today. It records the dance, but it is not the dance.

This is because body-to-body is also mind-to-mind. As most

experienced iaidoka know, the kuden (spoken tradition) is as important

as physical training.

Though my study of sword forms is unique and necessarily small, it

always impresses me to see someone else do Muso Shinden Ryu, for

example, and to easily recognize kata. Instructor Phil Ortiz

recently treated one of our New York Budokai classes to old film of

Otani Sensei and several other teachers of Muso Shinden Ryu and

Tenshinsho Jigen Ryu iaido. He and I were both pointing out and

naming kata being performed. That is one of the beauties of

body-to-body (and mind-to-mind) transmission. We know it when we

see it, because we know it.

All this assumes that the teacher is a qualified one who knows what

she’s doing. It's true that unqualified people can and do

establish themselves as teachers of various movement traditions.

In that case, a teacher could (a) simply not teach what she doesn't

know, and therefore stuff is lost; or (b) (my personal favorite) fill

in gaps with independently derived interpretations that (unless she is

clairvoyant) are probably not part of the original practice.

One does not have to look far to find over-interpreted aspects of stuff

creeping into people's practices (see Klens-Bigman, 1999). I have

seen videotape of Americans practicing some sort of kenjutsu with himo

(a thin sash) tied around their regular-sleeve keikogi. One ties

one's kimono sleeves back with himo to keep them out of the way.

If your sleeves are not in the way, you don't tie them. However,

some teacher saw the himo being used somewhere, thought it looked cool,

and decided to make it part of his school's uniform for kenjutsu,

without knowing its proper function. However, one person’s cool

is another person’s silly.

While costume elements are a benign aspect of invented tradition,

techniques can be invented as well. We were once introduced to a

kumidachi practice, wherein one of the kamae involved holding the sword

horizontally above one's head. For that reason, Otani sensei

referred to the kamae as torii - that is, the gate found at the

entrance to Shinto shrines. Unfortunately, he only showed us the

technique that one evening, then disappeared on one of his long

business trips to Japan. The sempai who took over responsibility

for teaching, with not much more experience than we had, could not

remember the technique properly and filled in the gaps himself.

What started as "torii" became "toriai" and took on a different

character than what we were originally shown. Eventually, it was

dropped from the repertory, since none of the sempai could agree on

what its function was, let alone what it was called. We chose to

abandon, rather than reinvent the technique, and it was probably just

as well.

The beauty of the Flos lies in its sparseness, but it is also a

danger. There will always be a lack of depth to picking up a

Medieval fighting manual since we can never know the social milieu that

produced it, even if, with many years of work, we are able to replicate

the techniques we see there to some extent. Nature, as they say,

abhors a vacuum, and Charron, to his credit, is trying like hell not to

give in to the temptation to fill it. But it's frustrating.

However, in a Japanese martial art that has enjoyed some kind of

continuous practice, a certain, perhaps small amount of that mindset

might still exist in what is passed down through generations of

practitioners. It is not only the movement that is being passed

along, it is also the verbal vocabulary, and the mental/philosophical

underpinning that is being passed along too. In his exhaustive

study, Miyamoto Musashi, His Life and Writings (2004), Kenji Tokitsu

interviewed several contemporary practitioners of Niten Ichi ryu, the

style Musashi founded. Tokitsu hoped to establish some idea as to

what was in Musashi's head in determining some of the more cryptic

parts of the his Book of Five Rings through the sword techniques as

they have been handed down. Though Tokitsu in no way resolved

some of the enigma that surrounds the work, the insights of the

teachers he interviewed give us some idea of where Musashi may have

been coming from - more so than if Tokitsu had confined himself to

manuscripts alone. Moreover, the evolving, underlying reasons for

practicing martial arts continue to give meaning to contemporary

students, even if those meanings have changed substantially over time.

While there are plenty of puzzles behind old styles of martial arts, I

suspect those who practice a traditional Japanese martial art have more

clues to them by virtue of passed-along knowledge than someone who

simply comes upon Fiore's Medieval puzzle, armed with only a liberal

arts degree and the desire to dig around (even if it is along with the

best of intentions).

Is there a best solution to this dilemma, and if so, what is it?

Maybe it can be found in a tradition that has both written scrolls and

an uninterrupted, to the extent that is possible, lineage of

practitioners that together create an unbroken line of

transmission.

But, it depends on what is important to you.

If romance is more important, then it makes sense to pick out something

that interests you and invest it with the fantasy of your

choosing. There must be a Klingon batlith school out there

somewhere. (There are still one or two martial arts schools in

NYC - and probably elsewhere - whose techniques are based almost solely

on the martial arts movies of the '60's and '70's. Think about

it.)

If neither romance nor history is important to you, pick out modern

(i.e. sport) budo. Good exercise, fun and no mental heavy

lifting.

In the case of the Flos, Charron, if he ever hopes to realize his

recreation of Fiore's system, with have to come up with his own

meanings for practice, acknowledging that no amount of careful research

is going to uncover all of the secrets of 15th century Italy. The

techniques that he has researched seem to work on a practical level,

and informally, philosophically as well. Already he admonishes

students with "How's your elephant?" emphasizing stable body positions

as a part of practice. Publication of his interpretive efforts

has yet to come about, however. The Flos is like a set of nesting

boxes – take off a lid and there is another box inside. Moreover,

some of the boxes are missing altogether.

What about those of us who practice the descendants of the ancient

forms? I guess our consolation is (1) the techniques still work,

on myriad levels, with many meanings; and (2) we can point to our

ancient forbears, even though we cannot imitate them.

Note:

(1) Of course, interpretation of the extent of

‘creation” or re-creation” for these and other art forms remains in

flux. Most newer arts claim descent from earlier forms, whether

objective analysis backs up that assumption or not.

Bibliography

Donohue, John J.

1997 “Ideological Elasticity: Enduring form and changing function in

the Japanese martial tradition,” Journal of Asian Martial Arts, 6:2,

10-25.

Klens-Bigman, Deborah

1999 “Borrowed ritual, invention of tradition: the

construction of the ‘traditional’ martial arts dojo” http://ejmas.com/proceedings/GSJSA99klens.htm

2003 “The Flower of Battle: An Interview with Bob

Charron” (parts 1 and 2).

www.fightingarts.com.

Knights of the Wild Rose

n.d. Flos Duellatorum (Pisani-Dosi (Novati)

version). www.varmouries.com/wildrose/fiore

Lowney, Chris

2005 A Vanished World: Medieval Spain’s golden Age of

Enlightenment NY:Free Press

Tokitsu, Kenji

2004 Miyamoto Musashi – His Life and Writings Boston:

Shambhala Pub.

Our

Sponsor, SDKsupplies